Ledgernomix

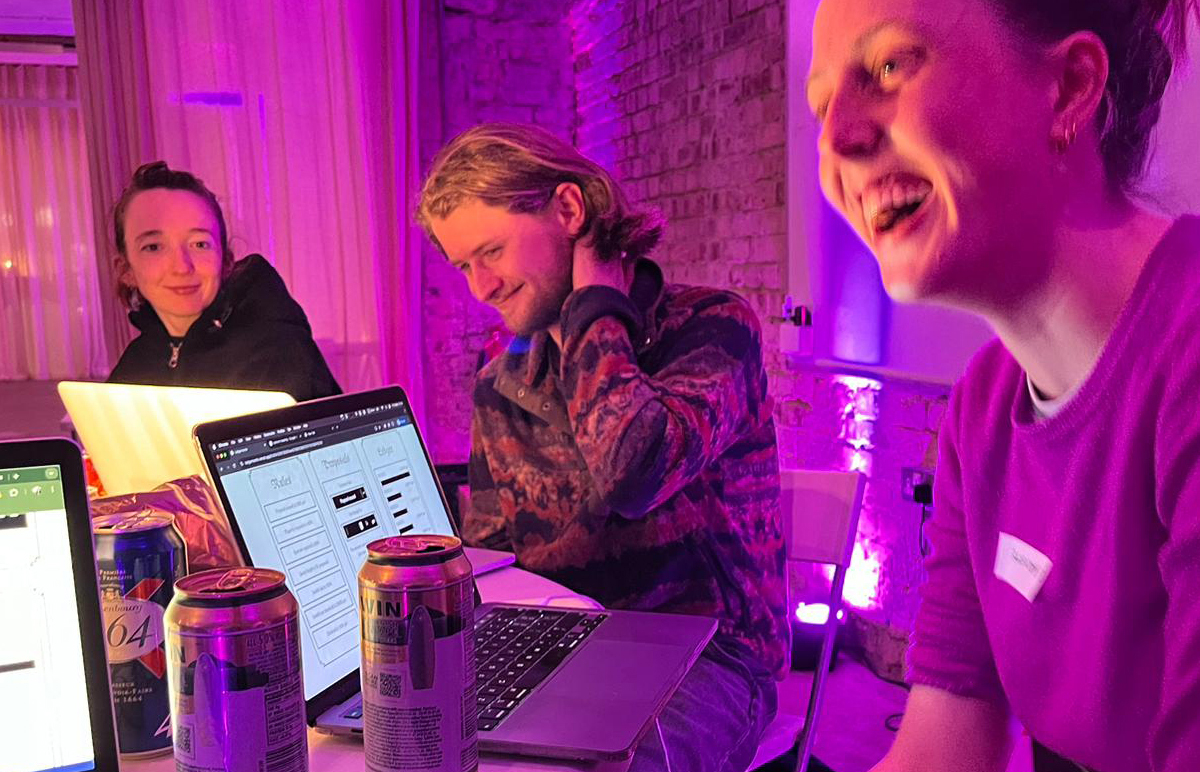

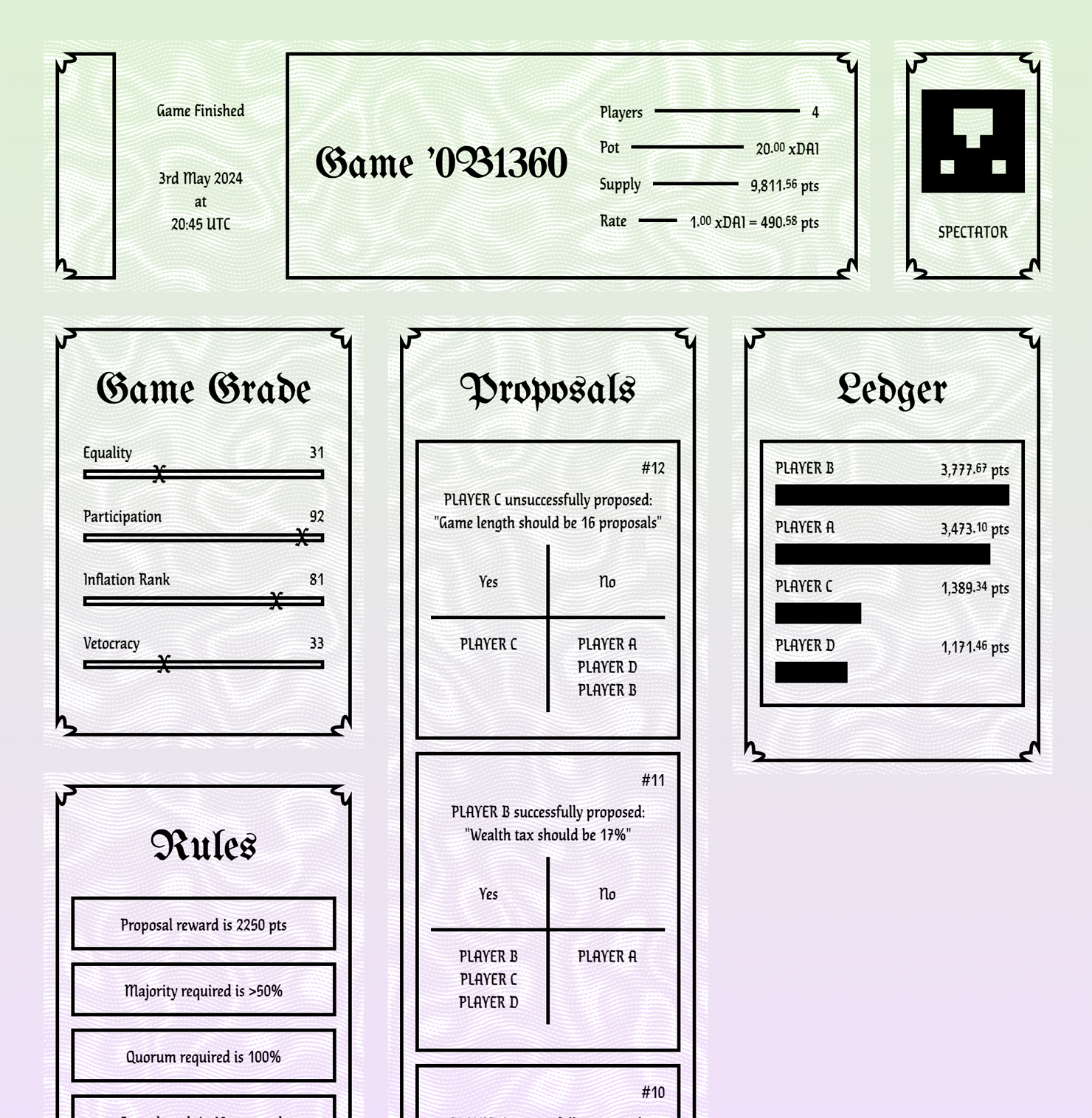

2025-04-21Ledgernomix is a game I made with Tom Chambers. We launched it with an event at Newspeak House in London in May 2024.

It’s a game of political economy, played on a Blockchain with real cryptocurrency.

Each game of Ledgernomix is a distributed autonomous organisation, or DAO, governed by a contract that exists on the blockchain. It can also be looked at as a self-contained model economy and model parliament.

The players buy in by staking a few dollar’s worth of cryptocurrency when they join the game. These joining fees become the game’s pot.

Players take turns to propose changes to the game rules, engage in debate and persuasion, and then vote on the proposals, according to the rules they’ve established. During the game, points are issued to and deducted from the players, again, according to the rules they create. You can think of the points as that game’s own currency.

At the end of the game, the original pot of cryptocurrency is redistributed among the players in proportion to the distribution of points in the game. Games are also ranked on various subjective criteria for success – Equality, Participation, Inflation, Vetocracy.

Ledgernomix is influenced by Peter Suber’s game Nomic and Lizzie Magie’s The Landlord’s Game (AKA Monopoly).

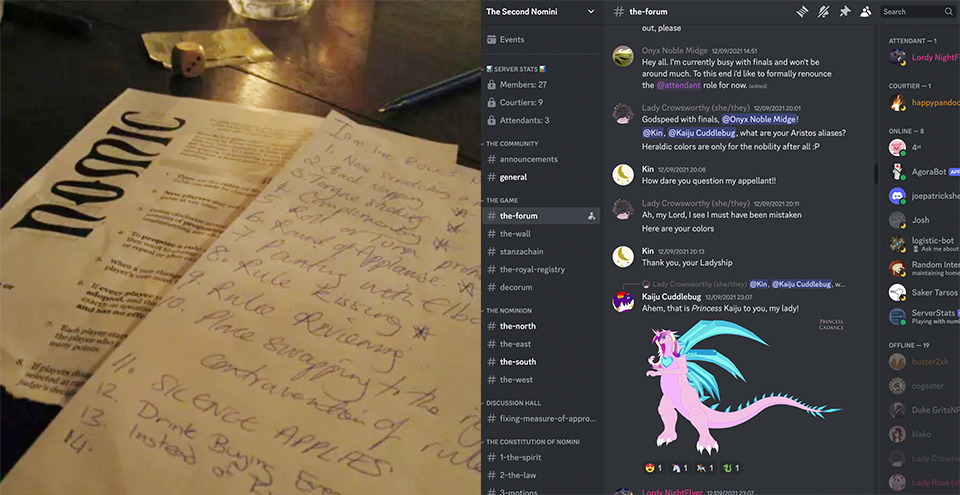

Created in 1982, Nomic was the original game of the rules of the game.

As Peter Suber describes it:

“Nomic is a game in which changing the rules is a move. In that respect it differs from almost every other game. The primary activity of Nomic is proposing changes in the rules, debating the wisdom of changing them in that way, voting on the changes, deciding what can and cannot be done afterwards, and doing it. Even this core of the game, of course, can be changed.”

People continue to play Nomic today, on paper and in online groups, which can develop ridiculously esoteric bureaucratic structures. Our game Ledgernomix is necessarily much less free in form, as all the rules are defined by changing parameters in the blockchain code. However, its existence on the blockchain also gives the game a life of its own, beyond the players’ control. We observed that having “real” money at stake, even in small amounts, changes the social dynamic.

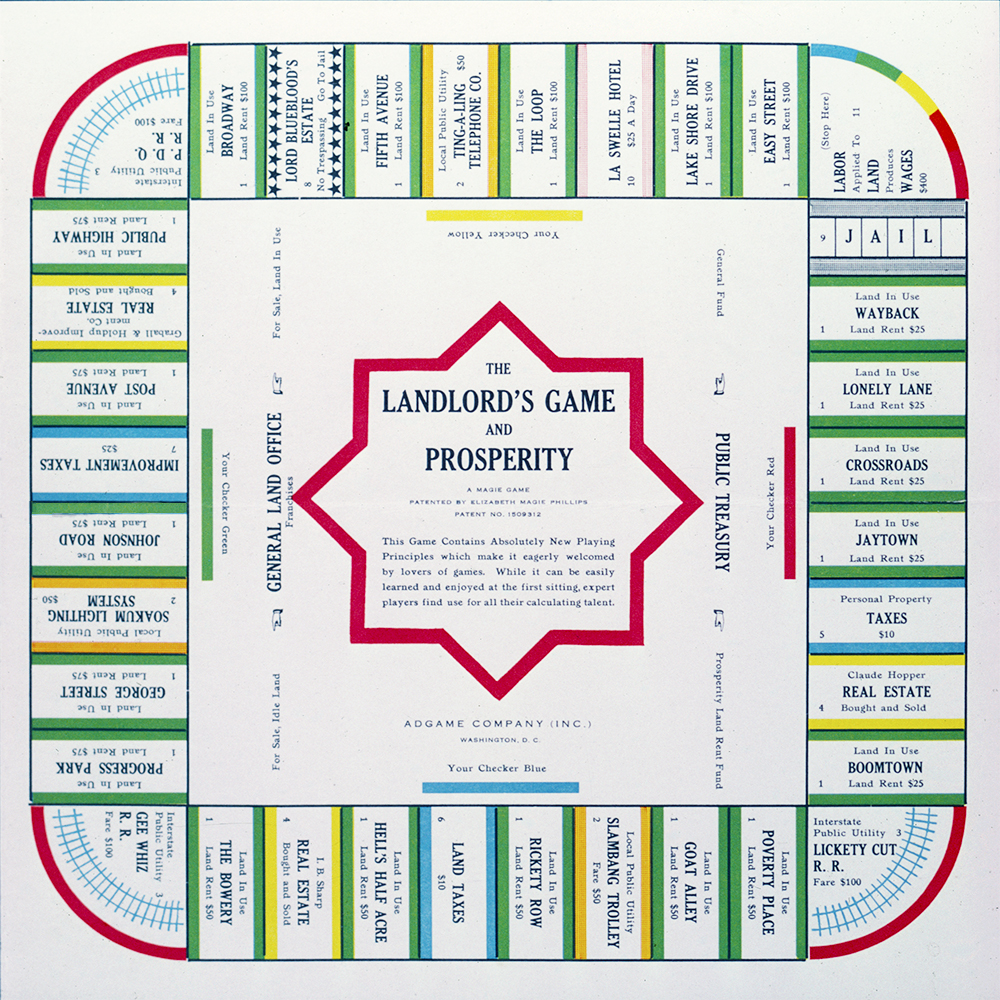

As a game about money, Ledgernomix owes something to Monopoly, or more accurately, to The Landlord’s Game.

That game was originally created by Lizzie Magie to promote the ideas of economist Henry George around land value tax, and she had two sets of rules – one where properties could be bought up and rents extracted until one runaway winner emerged, and another where land was held in common and rents paid to all, which she called Prosperity.

Obviously, it was the former version which became popular, first as a folk game in certain circles, and then as a commercial success when it was passed off by Charles Darrow and Parker Brothers as their own invention, “Monopoly”, in 1935.

I think the more equitable economic system Magie imagined might have been better in life but less fun as a game. In contrast, Ledgernomix doesn’t have two distinct sets of rules – players change the rules continuously, directing it towards winner-takes-all fun or more idealistic goals if they choose.

Aesthetically, I started by referencing founding documents, manifestos and constitutions. Another influence was the card game collectible aesthetic for digital goods which was emerging during the pandemic when we first started work on the game.

I was also thinking about Scott Alexander’s influential 2014 essay Meditations on Moloch, where Moloch, a god described in the Bible that demands human sacrifice, is used as a personification of the dynamics which force people to compete when they’d be better off co-operating.

Through the lens of Moloch, creating a decentralised system is like summoning a demon with a will of its own. This idea isn’t entirely new to the blockchain space – MolochDAO is a framework for issuing grants for research projects that leans in heavily to this aesthetic. I hope that the look of the Ledgernomix interface hints at some of that demonic potential.

While Ledgernomix is intended to work as a game – to be fun to play – it’s also an art project about the possibilities and pitfalls of decentralised systems. The game necessarily presents an extremely simple model of an economy. The aim isn’t to say that this or that system or rule would be bad or good in the real world. Experimenting with the system is the point, to observe the changing relationships between rules and people, and to watch the gap between intentions and outcomes.

Copernican Camera: Rotation 3

2022-12-22

Below is a small, very sped-up version of the third full loop I’ve shot with the Copernican Camera, a motorised camera mount I made to bring a non-geocentric perspective to an everyday context.

I originally shot this loop at home in Dumfries in 2020, commissioned as part of a short film Our Night Skies produced by Lumen, and screened at An Lanntair in Stornoway as part of the Hebridean Dark Skies Festival in February 2021.

You can read more about the Copernican Camera here: Copernican Camera Version 2

Loops in BayeuxSpace

2019-05-30

A collaboration with Tom Chambers of Random Quark

These videos are generated by a neural network trained on images of the Bayeux Tapestry.The process of changing a trained network’s input parameters and observing the output is often described as exploring a space. In that sense these animations are looping paths within that space.

Extending the Bayeux Tapestry is a task that has been attempted before by human minds far more informed than any of the machine learning models we experimented with. The tapestry has been repeatedly revived and claimed and drafted in to bolster various causes at different points in European history (and so it continues), but the human tendency to identify with one side or the other isn’t always helpful.

Algorithms can generate new imagery naively, on a purely visual level, indifferent to the features we’d see as being loaded with meaning or constituting narrative, and unthinking when it comes to context. We thought it was possible that the machine’s distance from the subject matter could give it some apparent insight – generating images of meaningless conflict without heroes or villains, justice or honour.

The entire tapestry constitutes a very small dataset in machine learning terms. Our trained network suffers from “overfitting” – rather than demonstrate a general understanding it tends to generate images that can be traced back to particular scenes in the original. However, it still produces some interesting intermediate states in the space between those scenes.

Copernican Camera: Rotation 2

2018-11-17

This video is the second full loop I’ve shot with the Copernican Camera, a motorised camera mount I made to bring a non-geocentric perspective to an everyday context.

The first time it was in Scotland following the stars, this time it was tracking the sun from a pub in North London called The Happy Man.

In May, just after shooting and editing the second loop, I showed both videos opposite each other, as well as the machine used to make them, as part of an exhibition called Cosmic Perspectives at Ugly Duck gallery in Bermondsey.

I’ve written a little about the machine and the ideas behind it here: Copernican Camera Version 2

Mis-en-a-Z Ⅰ, Ⅱ & Ⅲ

2018-11-02

The black circular frame occupies the same plane as an image of itself – the conflict between the two surfaces causes a glitch called z-fighting or stitching which changes as they move relative to the camera, generating complex patterns.

This was made with Processing, and if you want to play with the code I’ve posted an earlier version on OpenProcessing here:

https://www.openprocessing.org/sketch/570976

To create these GIFs I split my original code into two versions. I rendered the glitches at a lower resolution and framerate, making the pixel-scale patterns more apparent. Then I scaled them back up and combined them with a smoother, higher resolution version of just the circles-within-circles without the z-fighting.

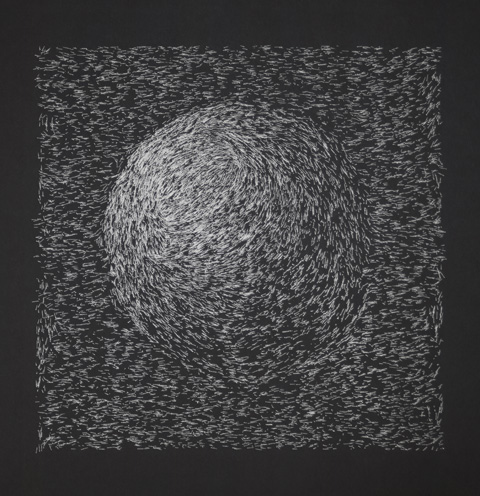

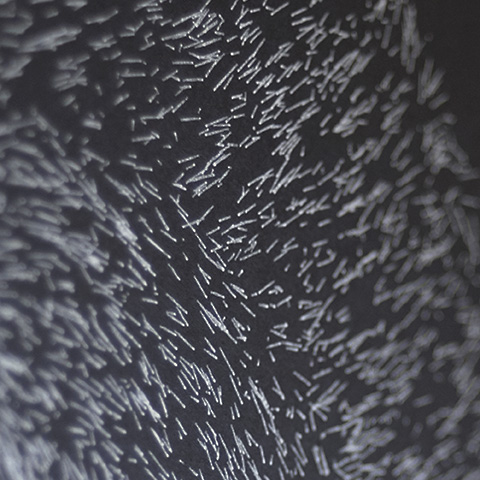

The Four Solids Plotted

2016-12-03

These are plots on paper of some of my algorithmic drawings, made using a customised 1980s pen plotter. The plotter draws as the program is run, and there’s a lot of randomness in there, so they turn out differently each time. The teapot will still be a teapot, but its edges and texture will shift, so these are somewhere between editions and originals. I’ve included two plots of the cone here to illustrate the variation.

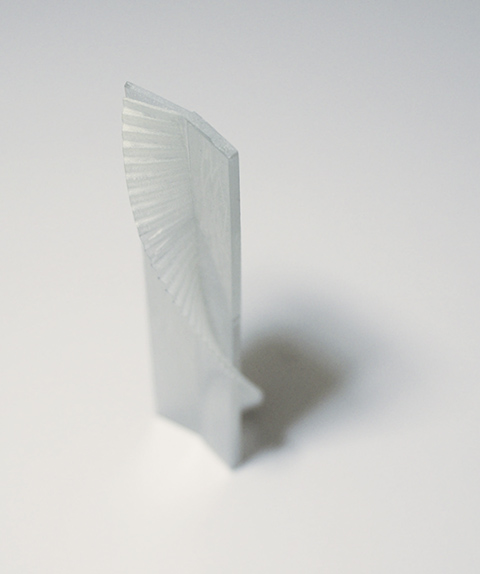

Clock Helix 1

2016-08-21

This 3D printed sculpture shows a two dimensional clock face, with time represented as the third spatial dimension. The structure is fixed but a moving laser highlights a particular cross section of time. This version is just 15cm long, and represents 40 seconds. At this scale, a 12 hour version would be 162 metres long.

I was building on the idea from an earlier work: 2D + t: 10:00 AM

The GIF on the right is a quick fast-forward scan of the shape. The video at the bottom is a brief clip at 1 second per second, with sound.

Copernican Camera Version 2

2016-07-13

This is how the Copernican Camera looks in its most recent version. There’s a spirit level and a compass built in, so it can be lined up with the celestial pole. The angle of the bend is set to 51 degrees for London’s latitude.

The idea behind the project was to bring an non-geocentric perspective to an everyday context. It’s also about closing the gap between “knowing” the fact “the earth rotates” and actually building it into one’s understanding.

There’s this story about Ludwig Wittgenstein, originally told by Elizabeth Anscombe:

He once greeted me with the question ‘Why do people say that it was natural to think that the Sun went around the Earth rather than that the Earth turned on its axis?’ I replied ‘I suppose because it looked like the Sun went around the Earth.’ ‘Well’ he asked ‘what would it have looked like if it had looked as if the Earth turned on its axis?’

This project takes that question at face value and offers an answer. Anscombe explains that Wittgenstein was actually making a point about language and the unsupported assumptions behind a phrase like “looks as if”. There are a lot of things that might be going on there, including the physical sensations that an individual has previously experienced while moving. The Copernican Camera takes just one aspect, the fixed visual frame of reference, and fixes it to the sun or the stars rather than the earth.

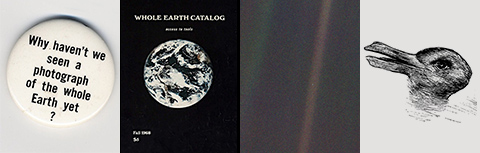

I’m interested in whether it’s possible, in reality, to see the earth “as” rotating, in the same way that we talk about seeing an ambiguous drawing like the duck-rabbit “as” one thing or another, and what else might follow from that. Stewart Brand, with his campaign for a photo of the whole earth in the 1960s, and Carl Sagan, with his “Pale Blue Dot” in the 1990s, both had idealistic visions of what an image of the earth from an astronomical perspective could mean. Both offered more of a top-down god-like view than the image sequences that the Copernican Camera captures.

I do think that images of the earth from space probably have contributed to a shift in attitudes, particularly when it comes to environmentalism, but I don’t think it’s easy to integrate scientific knowledge into everyday experience. I might say that I “know” that the sun is 93 million miles away but I’m just reciting a number. I don’t know it in the sense that I know my house is about halfway down my street, and I’m not sure what it would mean if I did.

The first video produced with the Copernican Camera is here.

Cover Art: “Honey & Skin” by Colour of Spring

2015-03-04Copernican Camera: Rotation 1

2014-08-14

I made this mount for a camera to compensate for the rotation of the earth, in an attempt to provide a non-geocentric perspective. The 4 second video loop below was produced from one day’s images.

The stars remain the fixed point of reference while the earth moves, as seen in the detail image from one frame. These motion-blurred frames were condensed from the original day’s sequence of still images, which was eight times as many, using slowmoVideo.

This rotation was shot near Dumfries in South West Scotland.